It uses freely available data, is reasonably straightforward to check and, remarkably, doesn’t just claim to be a good representation of past performance but can be used to predict the future.

In the old days of understanding, if your marketing efforts were working, you could easily work out your share of voice which in turn should be showing an improving market share, all things being equal. That was straightforward as you had a tight number of channels that you could measure easily against your competition.

The challenge that brands have now is that we run into a multi-channel problem. Brands have the opportunity to advertise on such a wide number of channels, ranging from your big-time TV campaigns to the hyper-targeted Facebook ads. Tracking what you’re doing can be straightforward, you hold that data, but maintaining tabs on the competition is getting more complicated given that they could be shifting from TV to YouTube, from email to TikTok.

The Share of Search metric assumes that all this activity, no matter where it’s placed, doesn’t start off with a click or a sale. The activity raises awareness for a brand and when a customer is in the state of mind to buy your product or service, they’ll head over to the high priest of the Internet, Google, and type in your brand name. So, the theory goes that if your share of voice across all these channels is high you’ll be more front of mind when to comes to the point of research for your customers.

This aggregated search data is saved, anonymised and placed for anyone to dive into at the Google Trends website. This data is usually used for Daily Mail stories around how popular Meghan Markle is, low-level trivia like that. In the last year, in response to share of voice becoming a harder metric to pin down, some very clever people, led from the front by Les Binet, have looked at trying to use this data in a more useful way.

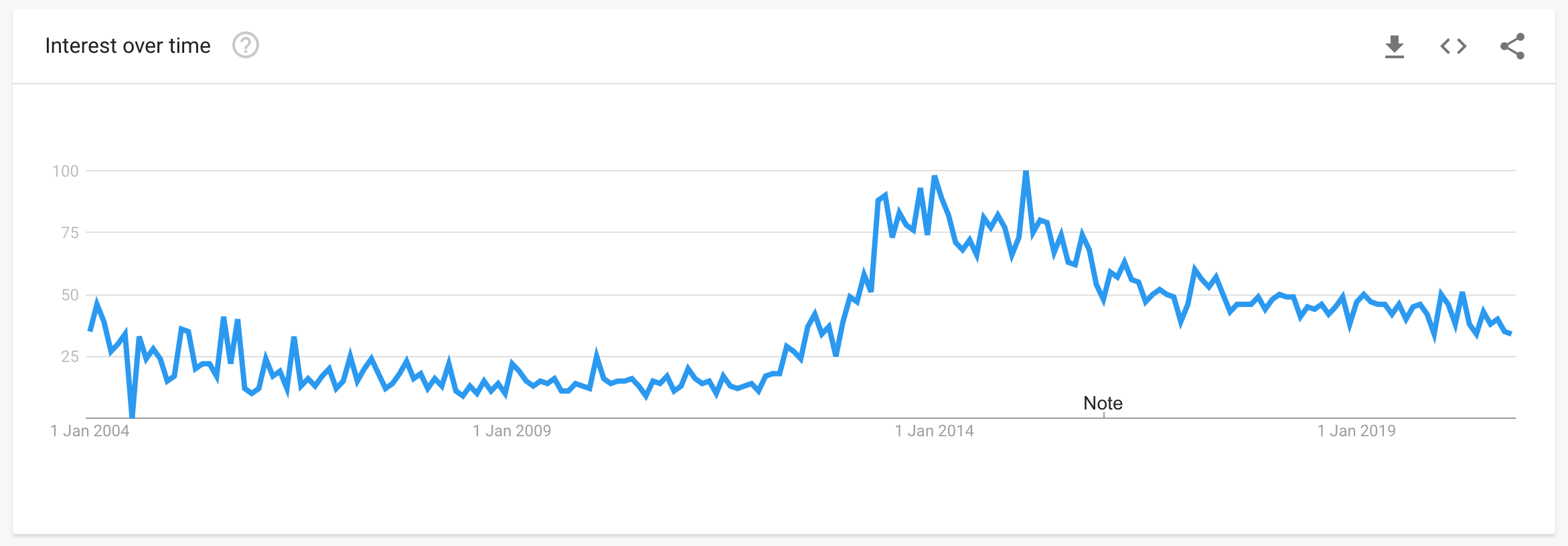

The principle is pretty straightforward, the more front of mind you are with your customers, the more likely they are to search for you on Google. You can use the data going back to 2004 and look at the way your brand has been shifting over time. So, here’s an example for a company we’ve been working with, just looking at their data. All we’ve done is enter their name:

The chart shows Interest Over Time. Google defines that as:

Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular. A score of 0 means that there was not enough data for this term.

So the chart shows interest with a rise in search interest around 2012. Nice. You can add competitors to this chart too.

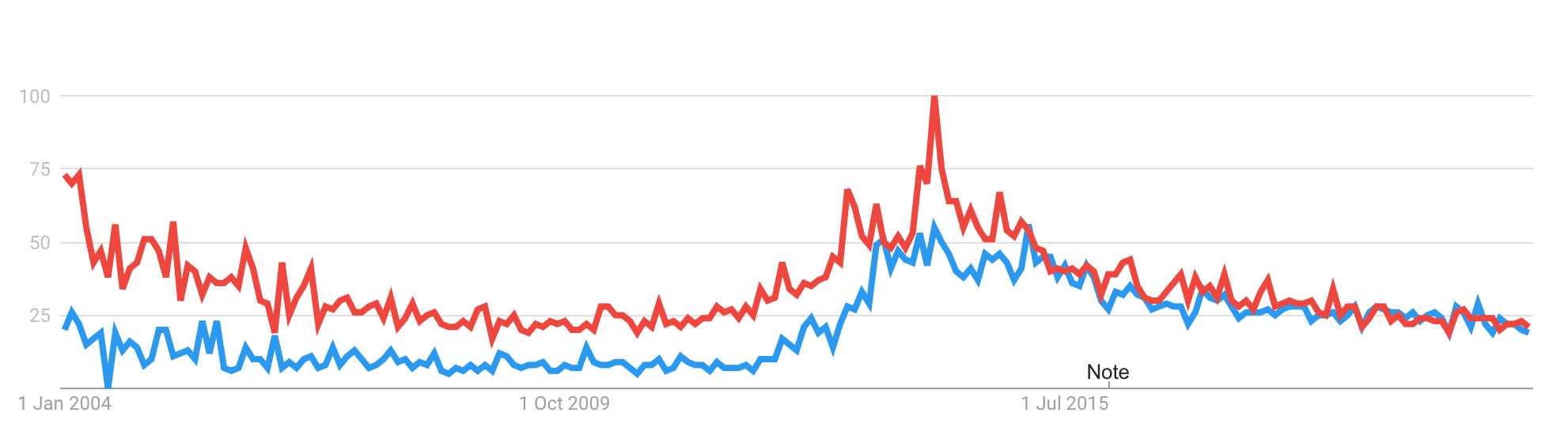

Here you can see that the competitor has had a stronger search interest but since around 2013 the interest has been around the same.

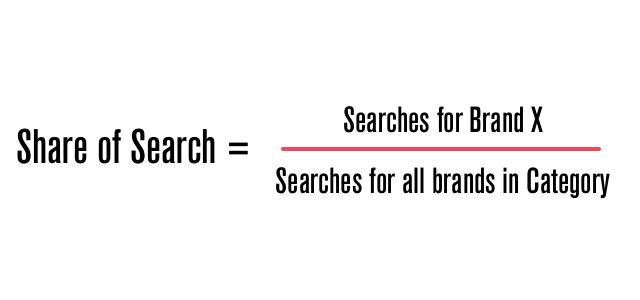

This is useful, but taking this from Interest Over Time to Share of Search needs a bit of Excel jiggery-pokery, taking the numbers and relative points and converting it into a percentage. The jiggery-pokery around this is nothing crazy, it just needs some massaging. Basically, it runs a moving average over the data and then tracks that as a percentage. The formula is:

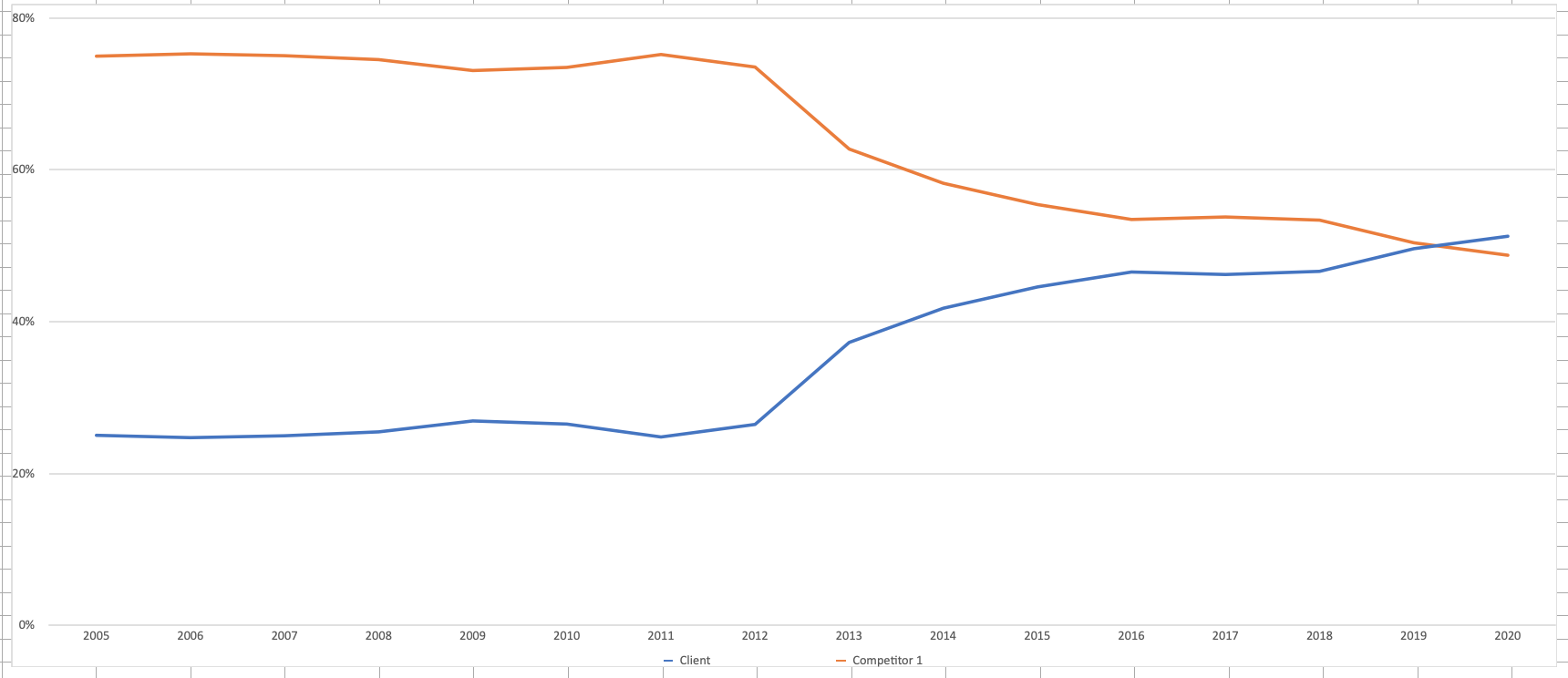

So once you run this through Excel, you get this output:

This chart, at the very least, is a useful conversation starter, and at the most, it can be a predictor of brand strength and, in turn, sales. We’ve been tentatively sharing this data with clients to help understand their brand-building efforts rather than the more measurable and big number bonanza that lives around performance marketing.

You can add five queries into Google Trends to get this data, you can use more in the charts but it needs a bit more pokery-jiggery to pull the data together.

Has Share of Search the new Share of Voice? Is this a new dawn?

Maybe.

There are some issues that you may need to watch out for.

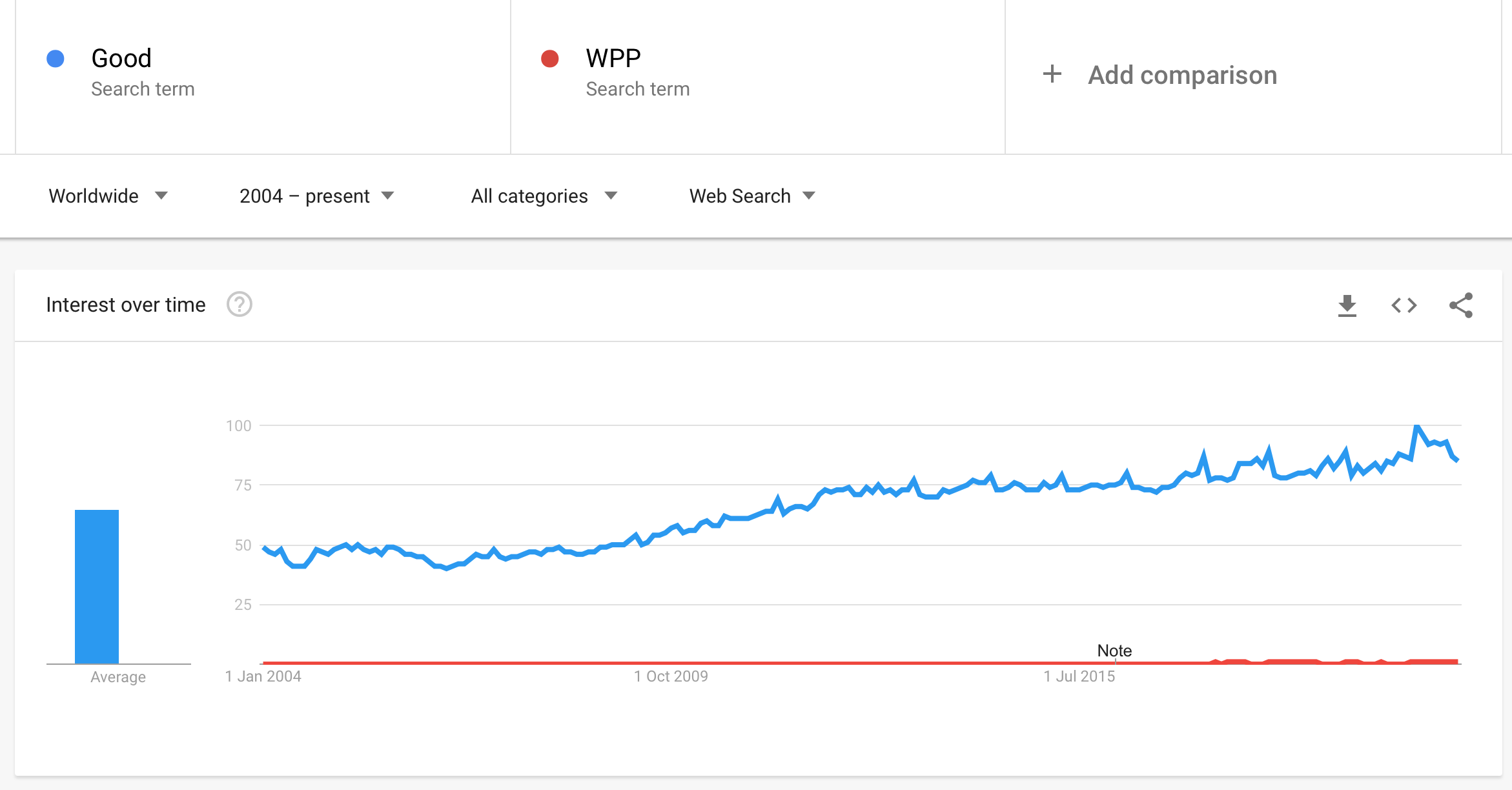

The first is one that we deal with. Our name. Here’s a Google Trends report for “Good” and “WPP”;

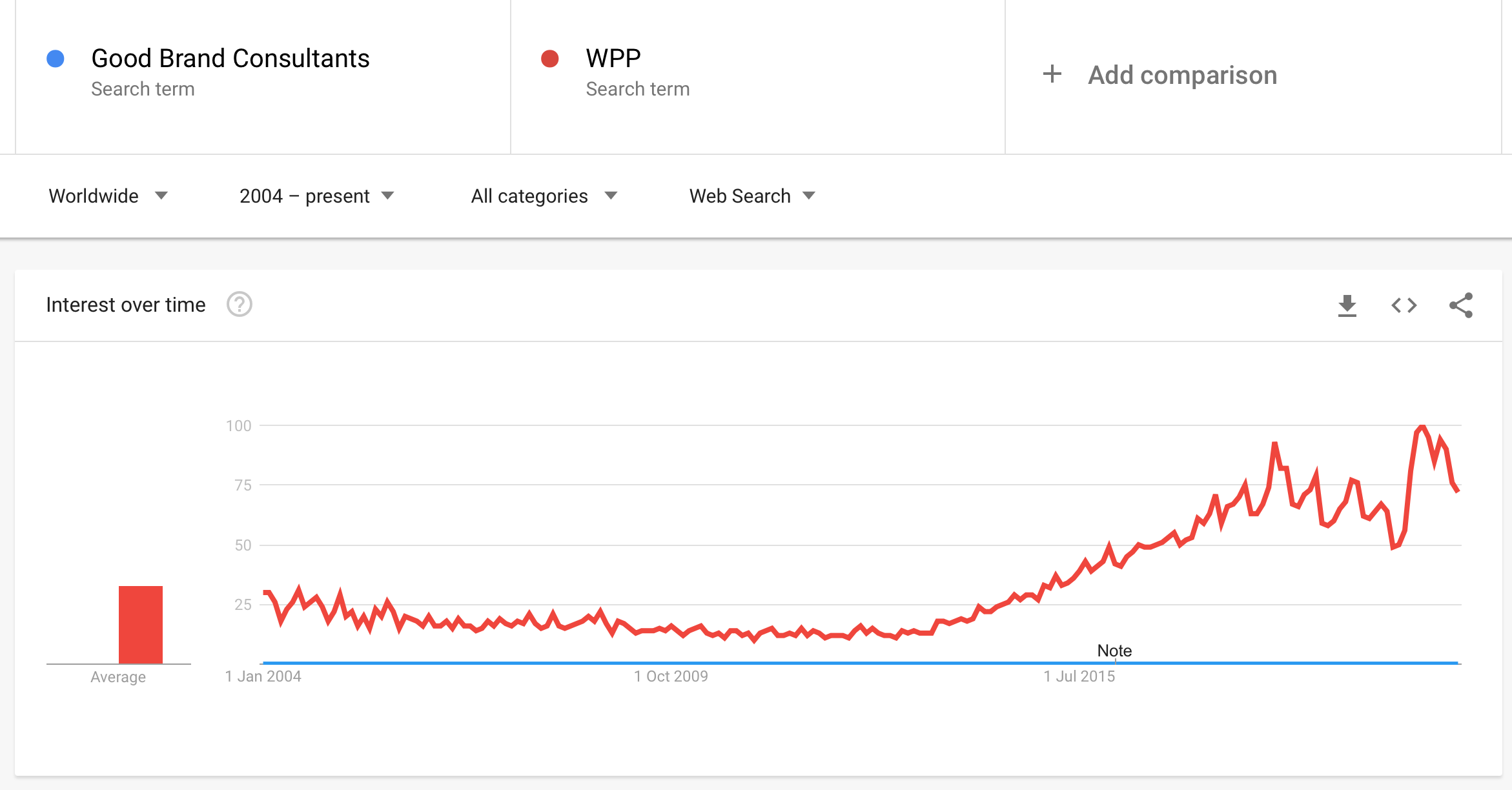

Does this mean that we’re of more interest than WPP? We’re certainly more interesting, but we’re clearly not responsible for this traffic. “Good” as a term is just too generic. To solve this you need to use context modifiers with your search query to make it more relevant to you. If we change our search to “Good Brand Consultants” you get a more realistic picture…

We’re still more interesting.

Using context modifiers is tricky, you need to make sure that they’re fair across the competitive set. If your brand name is “Twinkle Toes” and your competitor is “Xedaxtion”, it’s easier to get more accurate results from “Xedaxtion” than “Twinkle Toes”. To compensate for this you can then modify the search term around your category. So “Twinkle Toes” expands to “Twinkle Toes Vaccine” and the competitor search term changes to “Xedaxtion Vaccine”. It’s not as pure as a brand search but it can help with the category. Experiment to see what provides the best data. Best data being the fairest result, not the best result that confirms a bias.

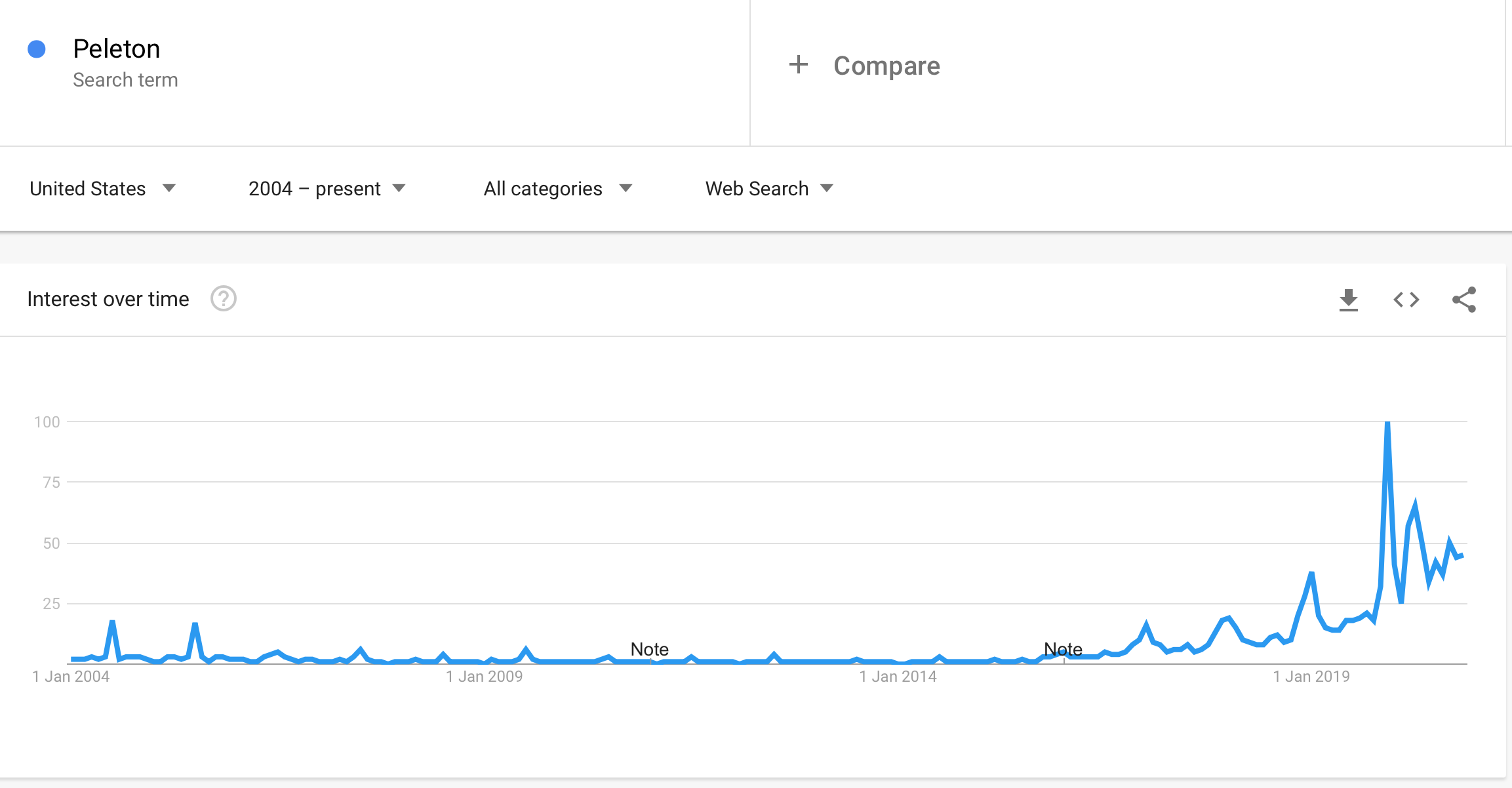

Sometimes you may be searching for a brand for what the brand would call the wrong reasons. Take a look at the Interest of Time results for Peleton.

They had a big old spike in December 2019. As ever, the data tells us what happened but not why it happened. Is the spike due to seasonal demand or was it due to the furore that the Peloton Christmas ad caused? The sentiment behind the search enquiry needs to be taken into account. Mr Benit has suggested that tying the sentiment from social media with the Interest of Time results could help mitigate the negative interest in the brand. Of course, it could be argued that no publicity is bad publicity. Did this harm or help Peleton? As ever, context is everything, use it wisely.

Share of Search from Google Trends data is looking like it could fill a gap in the reporting mix. It certainly isn’t going to replace serious brand tracking efforts, but it is an exciting complementary metric that can help guide actions and possible reporting on brand-building efforts. It’s still a nascent area of research though. Tom Roach gives a good analysis of share of search's potential shortcomings, it’s worth a read. So far though, we’ve enjoyed the conversations that Share of Search has been generating – it’ll be interesting to see how it grows over the medium term.

Want to start exploring? Here’s a basic spreadsheet that can convert the Google Trend data into Share of Search.